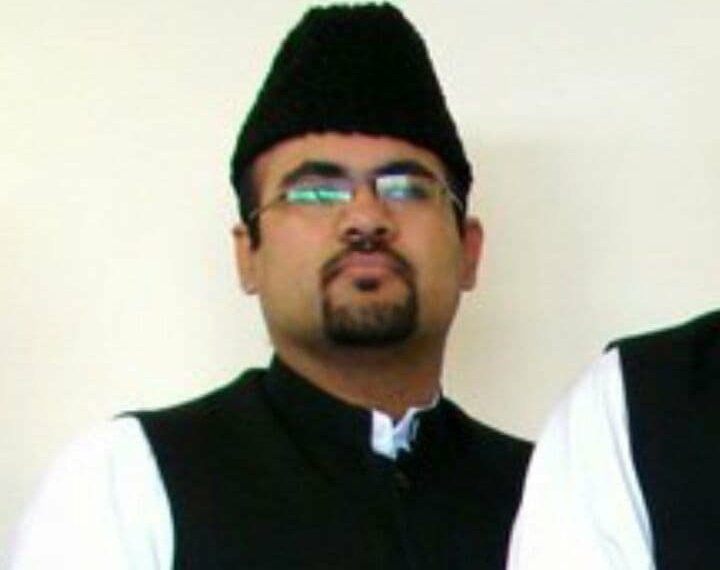

Author Salman Rushdie airlifted to hospital after attack onstage in New York state

Salman Rushdie, the author whose novel The Satanic Verses drew death threats from Iran’s leader in the 1980s, was attacked and apparently stabbed in the neck Friday by a man who rushed the stage as he was about to give a lecture in western New York.

A bloodied Rushdie, 75, was flown to a hospital. His condition was not immediately known. His agent, Andrew Wylie, said the writer was undergoing surgery, but he had no other details.

An Associated Press reporter witnessed a man confront Rushdie as he was being introduced onstage at the Chautauqua Institution and punch or stab him 10 to 15 times. The author fell to the floor, and the man was arrested.

Authorities did not immediately identify the attacker or offer any information about his motive.

State police said Rushdie was apparently stabbed in the neck. New York Gov. Kathy Hochul said later that he was alive and “getting the care he needs.”

Dr. Martin Haskell, a physician who was among those who rushed to help, described Rushdie’s wounds as “serious but recoverable.”

Event moderator Henry Reese, a co-founder of an organization that offers residencies to writers facing persecution, was also attacked and suffered a minor head injury, police said. He and Rushdie were due to discuss the United States as a refuge for writers and other artists in exile.

Lack of security questioned

A state trooper and a county sheriff’s deputy were assigned to Rushdie’s lecture, and state police said the trooper made the arrest.

But after the attack, some longtime visitors to the centre questioned why there wasn’t tighter security for the event, given the decades of threats against Rushdie and a bounty on his head offering more than $3 million US to anyone who kills him.

After the attack, spectators were ushered out of the outdoor amphitheater. Rabbi Charles Savenor was among the roughly 2,500 people in the audience.

“This guy ran onto the platform and started pounding on Mr. Rushdie. At first, you’re like, ‘What’s going on?’ And then it became abundantly clear in a few seconds that he was being beaten.”

After the attack, Rushdie was quickly surrounded by a small group of people who held up his legs.

Another spectator, Kathleen Jones, said the attacker was dressed in black and wore a black mask.

“We thought perhaps it was part of a stunt to show that there’s still a lot of controversy around this author,” she said, noting it soon became evident that it was no stunt.

Rushdie, a prominent spokesperson for free expression and liberal causes, is a former president of nonprofit PEN America. The group said it was “reeling from shock and horror” at the attack.

“We can think of no comparable incident of a public violent attack on a literary writer on American soil,” CEO Suzanne Nossel said in a statement.

Death threats followed the novel

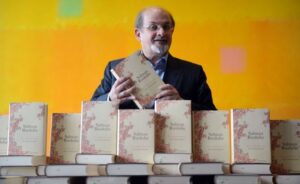

Rushdie’s book The Satanic Verses, first published in 1988, was viewed as blasphemous by many Muslims. Often-violent protests against Rushdie erupted around the world, including a riot that killed 12 people in Mumbai.

The novel was banned in Iran, where the late leader Grand Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini issued a fatwa, or edict, calling for Rushdie’s death in 1989. Khomeini died that same year.

Soon after, a wave of violence followed. Also in 1989, four bombs were placed outside of Penguin bookshops, one of which exploded in Northern England — Penguin being the British publisher of The Satanic Verses.

In 1991, The Satanic Verses’ Italian translator Ettore Capriolo was beaten and suffered knife wounds by a man who said he was Iranian. Less than two weeks later, Hitoshi Igarashi — who translated the book into Japanese — was stabbed to death by an attacker in Tokyo.

Iran’s current leader, Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, has never withdrawn the fatwa, though in recent years, Iran hasn’t focused on the writer.

Iran’s mission to the United Nations did not immediately respond to a request for comment on Friday’s attack, which led a night news bulletin on Iranian state television.

Rushdie committed to freedom of expression

The death threats and bounty led Rushdie to go into hiding under a British government protection program, including a round-the-clock armed guard.

Rushdie emerged after nine years of seclusion and cautiously resumed more public appearances, maintaining his outspoken criticism of religious extremism overall.

Novelist and professor of English at the University of Toronto Randy Boyagoda — who says he has interviewed Rushdie numerous times — said Rushdie’s commitment to freedom of expression is what guides his career.

- Salman Rushdie’s new memoir revisits life in hiding

He said that while the public focus on Satanic Verses and the violence and controversy that surrounds it is likely a “source of frustration” for Rushdie, he continues to speak publicly about the book, and the danger artists can face for speaking out, in order to champion the power of the written word.

“Here is someone who was not romantic about it — like, frankly, many of us are — but in fact, put his own life on the line to continue with his work,” Boyagoda said.

Rushdie himself has said he is proud of his fight for freedom of expression, saying at a 2012 talk in New York that terrorism is really the art of fear.

“The only way you can defeat it is by deciding not to be afraid,” he said.

Fatwa still stands

Iran’s government has long since distanced itself from Khomeini’s decree, but anti-Rushdie sentiment has lingered.

The Index on Censorship, an organization promoting free expression, said the money was raised to boost the reward for his killing as recently as 2016, underscoring the fact that the fatwa for his death still stands.

An Associated Press journalist who went to the Tehran office of the 15 Khordad Foundation, which put up the millions for the bounty on Rushdie, found it closed Friday night. No one answered calls to its listed telephone number.

In 2012, Rushdie published a memoir about life under the fatwa, titled Joseph Anton, which was the pseudonym he used while in hiding.

The Chautauqua Institution, about 90 kilometres southwest of Buffalo in a rural corner of New York, has served for more than a century as a place for reflection and spiritual guidance. Visitors don’t pass through metal detectors or undergo bag checks.

The Chautauqua centre is known for its summertime lecture series, where Rushdie has spoken before.

Courtesy: CBC News