Buddhist Monks Keep Getting Arrested for Corruption, Murder and Drug Trafficking

In June 2020, a woman was traveling in a van with her boyfriend when a pickup truck deliberately collided with them head-on at high speed. As she climbed out of the van and scrambled to escape the scene, she was chased down by the 59-year-old driver and stabbed repeatedly with a knife.

The truck driver later told the police in Buriram province, northeastern Thailand, that he had an affair with the woman, and had hunted her down after she allegedly blackmailed him, threatening to reveal their clandestine relationship. With two deep wounds to her head and one on her wrist, the woman—eight months pregnant—died at the scene. Her baby died too that day.

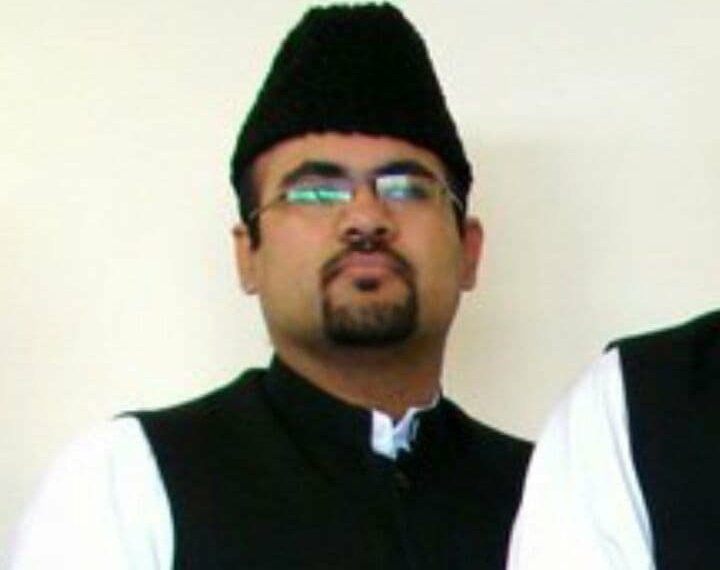

Their murderer was an abbot, the head monk, at a local Buddhist monastery.

The chilling case of the renegade monk grabbed national attention when it hit the headlines. But this wasn’t the first time members of the clergy had been caught committing a heinous crime in Thailand—nor is it as uncommon as one might think.

In Thailand, where Buddhism is the official religion and followed by about 93 percent of the population, the country’s 300,000-plus monks are historically revered for leading lives of moderation and being models of virtuousness. But the monkhood’s pious image has been increasingly eroded in recent years with a series of high-profile arrests and scandals.

Barely a week goes by without reports of monks charged with money laundering, drunk driving, drug trafficking and even murder—rocking the clergy’s reputation in Thailand with each new headline. With these scandals shining a light on the underbelly of monkhood, experts say that the sacred institution of Thai Buddhism is confronted with whittling public trust and legitimacy.

“Monks committing crimes is often reported in Thai media outlets, but it isn’t a recent social trend,” Katewadee Kulabkaew, a Thai Buddhism politics scholar and former visiting fellow at Singapore’s Institute of Southeast Asian Studies, told VICE World News. “This problem has chronically plagued Thai Sangha [the Buddhist monastic order] for decades.”

Criminality within the clergy has also been a region-wide issue for years. During the mid-2010s, Cambodia saw a wave of sexual assault and drug trafficking scandals related to monks, and similar cases have also been reported in Myanmar. In Thailand, many, including monks themselves, have spoken out about the criminality found within the walls of its Buddhist temples—from embezzlement to sexual misconduct against minors.

But despite calls to overhaul the system and government crackdowns to “purify” Thailand’s Buddhist institutions, the problem of renegade monks remains a prevalent one.

Just this month, Luang Pu Tuanchai, a monk who rose to fame in 2020 after claiming to have omniscient powers, was charged with drunk driving and drug possession. He had run a red light in his pickup truck, and when chased down by cops was found with a high blood alcohol level and dozens of methamphetamine pills. He was promptly disrobed. Earlier in January, another monk was similarly disrobed after being caught consuming methamphetamine pills and selling them to local youths.

“[These monks are] a victim of the society as well… [We] just point out that individual monks are bad, they’re this and that. But we have to ask, ‘What made them become like that?’”

Such criminality isn’t limited to the lower ranks of the Thai monkhood, with critics of the Buddhist institution in Thailand likening it to a “poisoned fruit.” While regular monks tend to make the news for violent and debaucherous offenses, those at the top of the Sangha leadership are more often embroiled in financial crime.

Although temples in Thailand are estimated to receive a whopping $2.8 billion in total donations every year, the majority lack proper accounting and are notoriously opaque about how those finances are distributed. And while monks are not allowed to accumulate personal wealth, it’s an open secret that some are rich—apparently having profited from the generous donations of temple goers.

It’s not uncommon for the hidden wealth of unassuming abbots to only be revealed upon their deaths. A couple of weeks ago, a deceased monk was revealed to have stashed over 10.6 million baht ($315,000) in cash under his bed, a shocking discovery that his relative only made while clearing out his home for the first time since the 81-year-old passed away in January.

Others don’t shy away from flaunting their lavish lifestyles. Wirapol Sukphol, a now-infamous monk, made headlines in 2013 when he was featured in a YouTube video sitting in a private jet with a luxury travel bag, holding wads of cash. The footage promptly sparked controversy over his ostentatious lifestyle, and subsequent criminal investigations led to charges for money laundering and sex offences.

The reasons for this apparent deterioration of monastic behavior are manifold, and experts point to the modernization of Thai society as an ideological culprit. Some note that in addition to the fact that mass and social media have made it easier to find out about and report on crimes, the rise of materialism and consumerism among the Thai people has also infiltrated Buddhist temples.

“[These monks are] a victim of the society as well,” Somboon Chungprampree, a social activist and executive secretary of the International Network of Engaged Buddhists, told VICE World News. “[We] just point out that individual monks are bad, they’re this and that. But we have to ask, ‘What made them become like that?’”

Besides the broad influence of Thai society, observers also point to those flaws in the monastic administration itself to explain why so many monks are veering off the path of righteousness.

Despite sustained calls for reforms and state attempts to purge the Sangha of corrupt individuals, the institution still finds itself at the center of lurid scandals that have emerged over the decades.

“The most systematic and the deepest-rooted cause of monastic crimes is the incompetence of Thai Sangha,” said Kulabkaew. “Most monasteries lack a rigorous and effective mechanism to tame ex-hooligans or troublemakers.”

Under the Buddhist governing body, experts say, there are practically no barriers to entry or departure from the monkhood in Thailand, while monks often do not receive the comprehensive religious education that’s meant to detach them from worldly desires or sins.

“The ultimate goal of Buddhism is for the people to get enlightened, and not be attached to the material world… [But] most of the society is learning that not all those who are wearing saffron can be a holy or respectable person.”

As a result, Kulabkaew noted, some see monkhood simply as an easy way to procure food, shelter, and financial support without necessarily having to abide by Buddhist teachings. “Monastic life in Thailand has long been temporary,” said Kulabkaew. “So there are chances that youngsters with dubious backgrounds or even criminals get ordained as well.”

Meanwhile, some enrol in monasteries to get away from legal trouble. Exploiting a lack of background checks at temples, fugitives have been known to seek ordination as monks while attempting to escape prosecution for serious crimes. In 2019, a 40-year-old abbot in Suphan Buri province, central Thailand, was found to have avoided charges of attempted murder and illegal weapon possession for 15 years, after allegedly firing gunshots at people in the 2000s and then checking himself into monkhood. It wasn’t until Thai police launched a large crackdown on criminal monks that he was finally detected and arrested.

In a similar vein, there’s the widespread belief that getting ordained is a convenient spiritual cure-all to wrongdoings.

“A lot of people, like those who commit crimes or politicians, make use of Buddhism to their favor,” said Chungprampree, adding that some people seek ordination as a way to troubleshoot their wrongdoings and get “purified.” This is a form of merit-making, a fundamental Buddhist practice of accumulating good karma before one’s death and rebirth.

“Many Thais are obsessed with the idea that merit-making can compensate for when they have erred, as if crimes and merit-making are transactional,” reads a Bangkok Post op-ed published in January, shortly after a disgraced policeman, whose reckless driving killed a woman and stoked nationwide anger, got ordained at a temple. His entry into monkhood, just days after the road accident, was an attempt to make merit for the victim, he claimed.

As media reports of criminal monks continue to stack up, experts agree that the Thai Sangha is ripe for reform. Better vetting, proper monastic training, and a more rigorous monitoring system, they say, could all help to keep monks from going astray during their time in the temple.

“In order to solve monastic crimes, the reform of monastic education and administration is necessary,” said Kulabkaew, citing the need for formal checks and balances monitoring monastic finances, as well as better surveillance to monitor and discipline wayward monks.

But for now, the problem of criminal monks is an enduring sore spot in local Buddhism, and one that’s slowly chipping away at Thailand’s faith in its religious institution. Some think that this will have profound implications down the line for much of Thai society, where Buddhism is seen as a moral pillar and where it remains common for Buddhist Thai men to become monks at least once in their lives.

“Buddhism is considered one of the fundamentals of Thai culture. Thai Buddhism is influential to most people’s way of life since it functions as their spiritual anchor,” said Kulabkaew. “[But] public opinion nowadays is quite negative for the corrupt Sangha in general.”

Years of appalling clergy behavior in the limelight are already taking their toll on public faith. Monks are meant to demonstrate to believers what it means to lead a simple and virtuous life. But according to Chungprampree, this role of monks in Thai society is gradually being lost in the static of bad publicity.

“Monks should lead us to see that with simple lives, we can seek the ultimate truth,” he said. “The ultimate goal of Buddhism is for the people to get enlightened, and not be attached to the material world… [But] most of the society is learning that not all those who are wearing saffron can be a holy or respectable person.”

Courtesy: vice.com