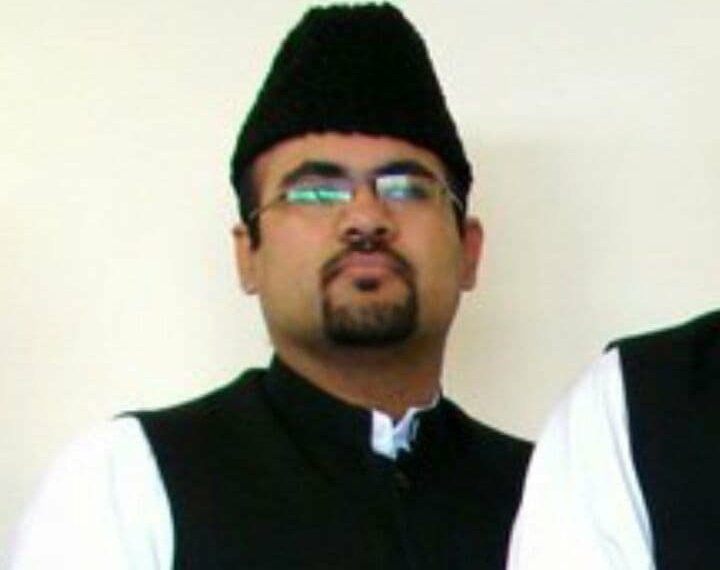

A priest overcomes India’s anti-Christian violence to lead interfaith dialogue

When riots engulfed Tiangia, a village in remote Kandhamal in eastern India, in 2008, Vikas Nayak was 15 years old.

Nayak sought refuge in the area’s dense tropical forests as marauding mobs of Hindu fanatics set fire to hundreds of Christian homes in his village. He heard the mobs chanting slogans as they killed Christians, attacked churches and torched properties using rods, swords, tridents, guns and kerosene crude bombs.

“Those images haunt me every day,” said Nayak, now 29, who spent three years in the tattered canvas tents of relief camps after the riots.

“Even though the camps were guarded by army personnel,” he remembered, “we were living in perpetual fear of more attacks and practiced our faith behind closed doors.”

After the savagery of the riots subsided, Nayak went to Varanasi to begin training as a priest. He immersed himself in spiritual discourses, meditation and Indian classical music.

The next few years of his formation were spent in different cities learning philosophy and theology. He visited families, organized youth prayer meets and spent time in prayer.

Last November, Nayak was ordained by the archbishop of Patna Diocese in the neighboring state of Bihar, becoming the first Catholic priest to emerge from a relief camp in Tiangia.

The Kandhamal riots of 2008 stand out as a watershed moment in India’s history of mass violence against minorities.

The flashpoint for the riots was the murder of a Hindu nationalist leader who is alleged to have been campaigning against missionaries and working to reconvert low-caste and poor Christians who had turned away from Hinduism to escape caste oppression.

Hindu extremists blamed the murder on Christians, even though it was widely believed to be the result of an attack by leftist insurgents. Christians were named “conversion terrorists.”

In the riots, more than 100 low-caste and Indigenous Christians were hacked to death or burned alive; more than 300 churches were demolished. Women were raped, religious texts were destroyed and Christians were forced to convert to Hinduism.

“Those memories can’t be washed away, but we mustn’t allow our ties to break further,” Nayak told a roomful of congregants who had turned up in colorful attire for his first Eucharist after his ordination.

In Kandhamal, where 59% of inhabitants live below the poverty line and depend on daily wage labor in agriculture, construction and domestic work, many families were expelled from their villages permanently.

Last year, the United Christian Forum for Human Rights reported 505 incidents of violence against Christians in the country, and the Evangelical Fellowship of India said anti-Christian hate crimes have doubled since 2014, when Narendra Modi became the prime minister.

Under Modi, minorities are increasingly being targeted and threatened, and attacks on pastors by Hindu extremists have become common. Not only are they prevented from holding religious services; they are regularly beaten up and charged with criminal conspiracy.

Nayak’s example has bolstered his former community during this difficult time for Christians.

After the 2008 riots, Nayak fled his village but had no idea whether his family had been captured by the rioters. After hiding in a forest for a fortnight, he walked miles to find shelter at a village school. A month later, he found his way to a relief camp for survivors in a neighboring district.

There, Nayak immersed himself in prayer and tried to stitch his life back together amid other displaced families that had been evicted from their villages and farmlands by irate Hindu mobs. He wrote about living like a refugee in his own land.

“I met my mother and sister after a year almost,” he said. “We didn’t want to go back to our village since the syncretic fabric of our society had been completely shattered.”

Nayak, who’s from a poor family of paddy cultivators himself, saw community bonds splinter.

The Catholic priest’s resolve to serve his community crystallized after the death of a senior pastor, the Rev. Bernard Digal, who was brutally beaten in the Hindu rampage.

“Father Bernard had dedicated his life to poor tribals and marginalized people,” said Nayak.

With states now enacting draconian laws against religious conversion, Christian leaders are worried that they will again be targeted. Missionaries have long been accused by extremists of forcibly converting low-caste Hindus by offering them money and bribes.

The Rev. Manoj Nayak, another priest from Tiangia but who is unrelated to Vikas, said Vikas Nayak’s resilience is admirable.

“Vikas is a gifted preacher who can spiritually strengthen our community,” Manoj Nayak said. “He can also boost the morale of those who’ve been stripped of work and educational opportunities.”

Noted human rights and Christian political activist John Dayal said the traumas Nayak faced in the relief camps have helped him look at the world with a more philosophical lens.

“It’s a triumph of the human soul to overcome such tragedy and go back to serving your community,” Dayal said. “Riot survivor-priests like him will be our new teachers and animators.”

In Kandhamal, the Catholic priest wants to bring faith leaders together, to restore peace and soothe communal divisions that have grown in the riot district over the last decade or so.

Every summer, Nayak visits his village, taking note of the rise in militant processions and sloganeering by right-wing groups. He also marks the profusion of temples and Hindu shrines on roadsides, Hindu symbols on street corners and saffron flags of the Hindu Party.

Still, he goes about his priestly duties, visiting families and offering spiritual and psychological support to those in need. At the end of every visit, he pays homage to Tiangia’s riot victims at the yellow-stone memorial near the main church of the village.

“Vikas offers hope to those who are even today traumatized to return to their native villages. He’s the face of interreligious harmony,” said a local priest, the Rev. Purushottam Nayak.

Vikas Nayak isn’t free of the fear of communal rioting every Christmas and Easter in Kandhamal. He worries for the safety of his family, his own life and the worsening of Hindu-Christian ties.

“I tend to be an optimist,” he said. “There’s a silver lining inside Kandhamal’s core, and the only way to move forward is to forgive the persecutors and reconcile with our past.”

Courtesy: RNS