ANALYSIS: Dalit Politician Shaking Up Uttar Pradesh’s Elections

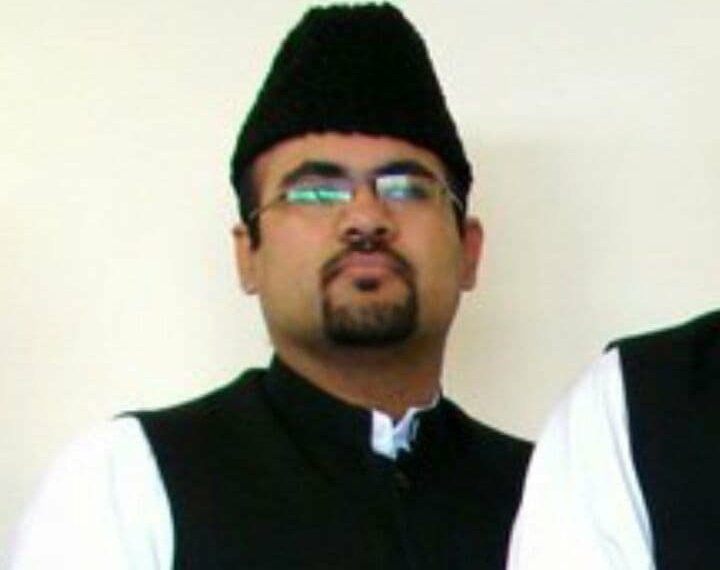

A massive crowd waits at an electoral rally on Feb. 5 in Gorakhpur, Uttar Pradesh. Flags of blue, the color of India’s anti-caste movement, flash on a street brimming with people. Most have gathered for a glimpse of Chandrashekhar Azad, who is visiting this town for the first time as part of his campaign to win a legislative assembly seat in Uttar Pradesh’s elections. Atop a flashy red car and wearing his flagship blue scarf, Azad arrives, twirling his moustache and waving to the crowds—things a Dalit person like him can be killed for.

Such is Azad’s charm. In a town he’s never visited before, he rebrands himself and his marginalized caste identity as a proud, mustache-twirling one.

The Indian subcontinent has the most rigid, oldest-running social hierarchical system in the world. This caste system places Dalits (formerly known as untouchables) not just at the very bottom of society but fully outside of it, deeming a community of 200 million people impure and unworthy of social rights.

Yet Azad portrays himself almost like a movie star, arriving at protest locations on top of expensive cars, donning sunglasses and golden watches, twirling his mustache—all things people of his community don’t picture themselves doing.

Indian politicians often try to prove how minimalistic they are. Mahatma Gandhi was well known for wearing a simple loincloth, and many famous politicians wear khadi, an Indian textile made with hand-spun cotton. It was popularized by Gandhi during the Indian independence movement as a symbol of self-reliance.

However, Azad’s flashy attire and personality are very important to his Dalit community. They’re not just symbols of rebellion; they’re a glimmer of hope for many in marginalized communities: an image they, too, can aspire to.

In some ways, Azad’s image is in line with that of previous Dalit leaders, who have never concealed their prosperity—from economist B. R. Ambedkar’s suits and ties that served as inspiration for Dalits to educate themselves to politician Mayawati’s handbags, which allowed Dalit women to believe they could also have money and status.

But Azad, whose name literally means “free,” has taken the game of rebranding and reclamation to a new level.

Ghadkauli is a small village in Uttar Pradesh’s Saharanpur district. A billboard on the outskirts of the village is shocking enough to make you stop and stare for a minute. “The Great Chamars of Ghadkauli welcome you,” the sign reads. “Chamar” is the most common derogatory, caste-based slur used in the Indian subcontinent. Azad put up the billboard himself, reclaiming a 3,000-year-old caste slur under a new identity of greatness.

If you search the words “The Great Chamar” on social media websites, you’ll see hundreds of young people using some version of that as their handle. The style of Azad’s politics has a massive influence on the younger Dalit generation, who show up to almost all of his rallies.

Uttar Pradesh’s elections represent the world’s biggest democratic exercise in 2022. About 150 million people are eligible to vote to elect members to the state’s legislative assembly as well as the state’s next chief minister. As India’s most populous state, Uttar Pradesh is often called the road to Delhi, as the political trends there set the tone for national elections.

How the ruling Hindu nationalist Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) fares in Uttar Pradesh could determine how it will fare in India’s next general elections in 2024. Uttar Pradesh’s incumbent chief minister, Yogi Adityanath, is revered among extremist Hindu nationalists who make up a huge chunk of the BJP’s core voter base. How Adityanath fares in this election will help determine the future of both the BJP and Hindu nationalist politics.

Azad is running in the Uttar Pradesh elections for the first time. It is remarkable that he has chosen to fight against the poster boy of Hindu nationalism, Adityanath, in his home turf: the legislative assembly seat of Gorakhpur. Yet even in a district that has sent Adityanath to Parliament for five consecutive terms since 1998, Azad has won over a sizable fan base.

Azad’s massive following is not new. His journey started when he, along with activists Vinay Ratan Singh and Satish Kumar, started the Bhim Army in 2014, the year the BJP cemented its rise in India with Narendra Modi’s election as prime minister.

The Bhim Army is named after Dalit jurist, economist, and social reformer B. R. Ambedkar—the architect of India’s constitution and one of the anti-caste movement’s most prominent faces. It’s a nongovernmental organization that works on behalf of Dalits and other marginalized groups in India—including Adivasis, the Indigenous people of India who also fall outside the caste system, and Bahujans, a term for Other Backward Classes communities, who fall in the fourth (last) rung of the caste system—by opening free schools, helping with legal aid, and working to advance an anti-caste narrative.

Azad gained popularity in 2017 after hosting protests in the heart of New Delhi over anti-Dalit violence in his home district of Saharanpur. The Bhim Army has since made it a point to address all caste-based atrocities by reaching out to victims with a team first and then raising the issue on social media.

Although social media is a space traditionally monopolized by India’s dominant caste, the Bhim Army has managed to create a space of its own, with thousands of members and numerous Telegram and WhatsApp groups—making information accessible to society’s lowest strata. Azad’s massive youth appeal has made it possible for him to penetrate social media with a substantial fan following and large-scale social media presence.

It was this on-the-ground presence and grassroots activism that enabled Azad, sensing a void in Dalit leadership, to enter electoral politics in 2020, when he announced the creation of Azad Samaj Party (ASP).

In advance of the 2022 state elections, Azad began looking for major political support. The most logical avenue of support would have been Bahujan Samaj Party (BSP) supremo Mayawati, given that she has been the most popular face of anti-caste politics in India. However, it is well known in India that these two do not share cordial relations.

Azad’s next option was to find support from the Samajwadi Party (SP), a party well known for its Other Backward Classes voter base. However, after a few meetings between Azad and SP chief and former chief minister Akhilesh Yadav, the talks ended, and Azad announced ASP would be pursuing elections without any alliances.

Mayawati, India’s first and only Dalit woman chief minister, ruled the state for almost eight years, going down as one of the most powerful national leaders in India. Mayawati has a cult-like following in Uttar Pradesh among the Dalit population. But dogged by allegations of corruption, her presence has somewhat faded in the last couple of elections.

Mainstream media and politicians do not miss a single chance to talk up the divide between Mayawati and Azad. But most politicians in India come from dominant castes, and they are never questioned about why they do not join the same parties.

Caste is a very important part of identity in India because it determines one’s social capital. An important and oft-criticized phrase about Indian politics is: “In India, you do not cast your vote. You vote your caste.” The phrase is frequently used by oppressor-caste political thinkers and analysts, but in reality, there have historically been very few oppressed-caste political leaders and decision-makers despite their large population (more than 300 million Dalits and Adivasis). Political parties like ASP, BSP, and others are labeled as caste-based parties when they are merely acknowledging the existence of the elephant in the room.

Azad’s primary political goal is adequate representation for Dalits and other oppressed communities, a subject often ignored by mainstream politicians. He constantly stresses bhagidari (representation) in every speech and interview he gives. Yet although his party gives proper representation to candidates from all marginalized groups, they are not truly intersectional. Out of the current candidate lists that ASP has produced, 24—out of 165 total candidates—are women.

Despite Azad’s popularity, it seems unlikely he will win. The middle-aged Dalit-Bahujan populace retain their allegiance toward BSP, and ASP is fighting elections in Uttar Pradesh for the first time. However, just by attempting to challenge the dominant-caste Hindu nationalist narrative and run against the poster boy of Hindu nationalism on his home turf, Azad is paving the way for future electoral endeavors. It is clear that if Mayawati retires in the future, Azad will be the next face of anti-caste politics.

The way Azad has rebranded the Dalit identity and inspired Dalit youth will help push the anti-caste narrative to national politics, where it has long been missing from political discourse. Azad’s move to enter mainstream politics can force national political parties to talk about caste and provide Dalit representation in their own parties. For Dalit and Adivasi politicians, elections and politics are not just about winning; they’re about survival.

Suprakash Majumdar is a Dalit journalist based in India. He writes on social justice issues from a caste lens. Twitter: @SuprakashJourno

Courtesy: Foreign Policy